Interviewer: Marie Tesson, Founder & CEO of Journeys of a Lifetime

Interviewee: Jean-Pierre Renard, Highly Respected Burgundy Wine Expert

Over the years, Marie has built a network of passionate and exciting experts, bearers of France’s and Europe’s heritage in all its diversity. Continuing this captivating series, Marie has chosen to take you on a journey into a world that she particularly cherishes: the art of winemaking.

In this second interview, Marie connects with Jean-Pierre Renard, a highly respected Burgundy wine expert, to explore the intricate concept of terroir. Together, they delve into the roots of Burgundy’s AOC system, its historical evolution, and how the unique interplay of natural and human factors shapes the identity of these world-renowned wines. Through their conversation, they uncover the mysteries of Burgundy’s terroirs.

The Roots of Terroir in Burgundy

Marie: “Jean-Pierre, Burgundy is where the land speaks through the wine. The AOC system is its voice. Can you walk us through how this system intertwines the very essence of terroir with the wine’s identity? Why does a name like Chambertin resonate so deeply in the glass?”

Jean-Pierre: Traditionally, Burgundy wines have been known as “wines of terroir,” originating from well-defined parcels of land. However, this distinction by origin developed gradually over time.

Early Middle Ages: The flavor of wine began to vary depending on its place of origin. By the end of the Middle Ages, it became customary to vinify wines separately based on their specific vineyard sites (lieux-dits), though these differences weren’t commercially recognized at the time.

1419: Wines started being referred to in the plural, as in “wines of Beaune,” rather than simply “Beaune wine.”

15th Century: This period marked significant changes. In 1441, Philippe the Good distinguished between “wines from the good slopes” and “wines from lesser areas.” By the end of the Middle Ages, the concept of wine origin was well established, and the conversation around terroir wines became increasingly prominent.

The Soul of the Soil: How Nature and Humans Define Terroir

Marie: “What is a Terroir?”

Jean-Pierre: Burgundy’s terroirs are famously fragmented, with vineyards divided into numerous small plots, each possessing distinct characteristics. Terroir is a combination of natural and human factors, including soil, climate, topography, and human intervention—all contributing to a wine’s unique profile.

Natural Factors: The nature of the soil and subsoil, which can vary even within the same village, plays a crucial role. Factors like drainage, exposure, altitude, rainfall, and temperature significantly impact the quality and maturity of the vines and grapes. The selection of grape varieties has also evolved over time, with roughly five months from bud burst to harvest.

Human Factors: Humans are pivotal in shaping the terroir through vineyard management, such as pruning and trellising, as well as vinification and aging methods. Any alteration in these practices can profoundly affect the wine.

This dynamic interplay is why Burgundy produces approximately 60,000 different wines each year.

The AOC System: A Reflection of Terroir

Marie: “How could a classification be linked to the notion of terroirs?”

Jean-Pierre: To understand how the AOC system reflects terroir, we must look back at history. The origin of a wine is fundamental in Burgundy. The AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée) system, established in 1936, underscores the importance of origin by providing critical information about the wine’s region, village, and specific vineyard sites, known as “climats.”

Climats: The term “climat” first appeared in 1540 in Chablis. By the 18th century, vineyard origins became more firmly established, and broader appellations like “Beaune” began to decline.

Village Names in the 19th Century:

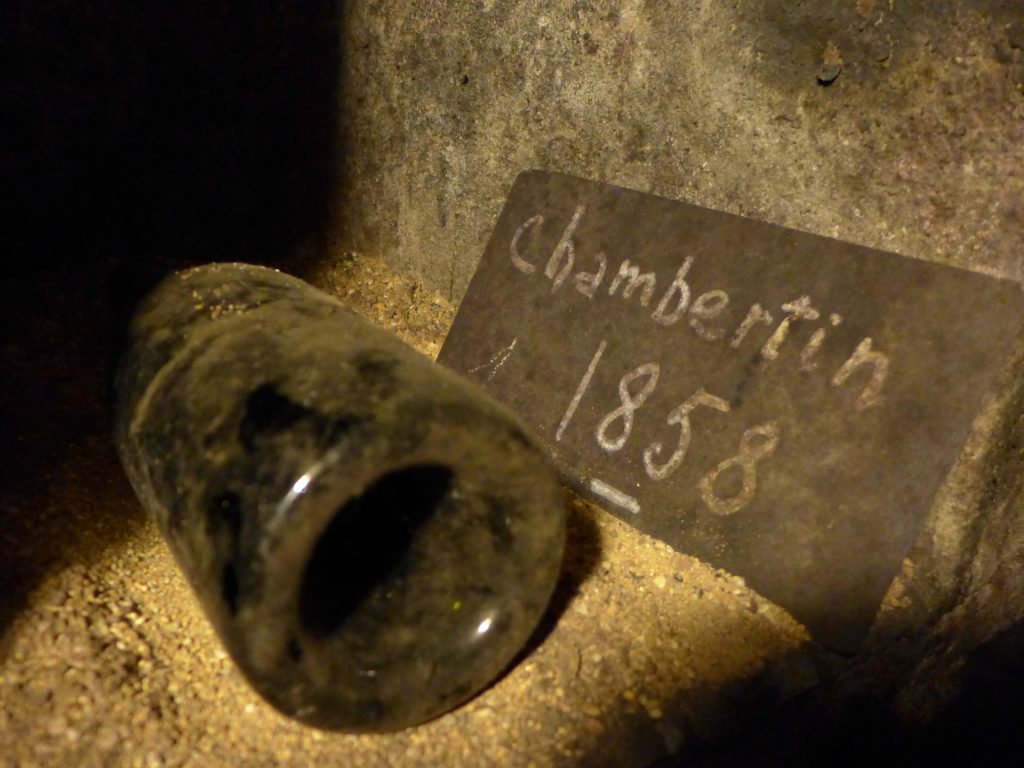

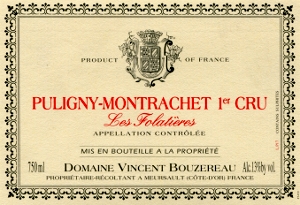

Before the 19th century, village names were simple, such as Gevrey, Aloxe, and Puligny, with no direct connection to specific vineyard sites. However, as vineyards like Chambertin gained fame—particularly under Napoleon I—villages like Gevrey renamed themselves “Gevrey-Chambertin” in 1847 to capitalize on the vineyard’s reputation. Other villages followed, such as Puligny and Chassagne, which added “Montrachet” to their names in 1880. Despite these changes, confusion remains today regarding the precision of appellations—whether they refer to a specific plot, a region, or the entire appellation.

Appellation System Emergence:

The late 19th century saw the devastation of vineyards by phylloxera, leading to the disappearance of many vines. To combat this, American rootstocks were grafted onto the vines, which proved to be a complex process. At that time, the average person consumed 100 liters of wine per year, but the phylloxera crisis drastically reduced wine production, leading to increased fraud and the importation of inferior wines.

1919: In response to widespread fraud, the appellation system was created, ensuring that wines labeled as coming from a specific place genuinely originated there.

1936: The AOC system was further refined, imposing strict regulations on grape varieties, yield, and production zones to limit abuses. This system has since become a global model, with similar protections adopted worldwide.

Unpacking the AOC Classification

Marie: “What exactly is the AOC classification?”

Jean-Pierre: The AOC system is structured like zooming in on a photograph, offering a closer view of the wine’s origin through three levels of appellation:

Regional Appellations:

These account for 50% of Burgundy’s production and cover broader areas with general characteristics. Sub-layers include:

- “Macon,” “crémant,” “coteaux bourguignons,” “Bourgogne.”

- “Macon Village,” “Bourgogne blanc,” “Bourgogne rouge,” “Bourgogne aligoté.”

- Additional geographical identifications like “Hautes Cotes de Beaune,” “Bourgogne Côte châlonnaise,” “Macon La Roche Vineuse.”

Village Appellations:

Representing 45 villages and 40% of Burgundy’s production, these wines express the terroir of specific villages, such as “Gevrey Chambertin,” “Pouilly Fuissé,” “Meursault,” “Puligny Montrachet,” and “Beaune.”

Grand Cru:

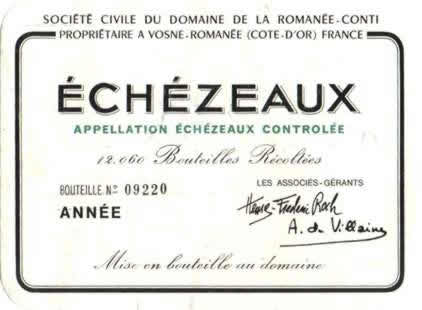

The highest classification, representing about 2% of production, Grand Cru wines come from single, very limited plots, like “Chambertin,” “Montrachet,” “Clos de Tart,” and “Romanée Conti.” They are often considered the best wines. However, this isn’t always the case. Some climats, like Meursault, Volnay, Pommard, and Beaune, may deserve Grand Cru status but have not yet been reclassified—a process that takes time.

Chambertin as an Example:

Chambertin serves as a prime example of a terroir so distinctive that it merits its own Grand Cru status. The vineyard’s soil composition, slope, and microclimate contribute to its exceptional quality.

Burgundy’s Classification Shift During World War II

Marie: “I’ve heard that WWII played a significant role in the AOC classification. What happened to the structure that was decided in 1936?”

Jean-Pierre: During the German occupation of France in World War II, a demarcation line was drawn after Buxy. The southern part of Burgundy, including the Mâconnais, was in the free zone, while the Germans confiscated wines from the northern regions. Due to low wine production in 1940 and 1941, the Germans extended their confiscations to village appellations. In response, Burgundy’s wine authorities created in 1943 a new level within the village appellations—Premier Cru.

Premier Cru:

Premier Cru wines are from the best parcels but still carry the village name. Today, they represent about 10% of production. However, some areas like the Mâconnais do not have any Premier Cru vineyards, as during WWII they were in the free zone and didn’t need protection. Other villages, like Marsannay, weren’t recognized as “village appellations” at that time, so they couldn’t have Premier Cru classifications.

Crafting Identity Through Terroir

Marie: “Burgundy winemakers are renowned for being the best advocates of terroirs, inspiring other regions. Can you elaborate on that?”

Jean-Pierre: Burgundy winemakers have long understood the importance of expressing the terroir of a single plot to give their wines a unique identity. Promoting terroir wines is crucial because these wines are of higher quality and can command higher prices due to their uniqueness. The recognition of Burgundy’s climates as UNESCO World Heritage sites underscores the growing appreciation for these terroirs. This model has inspired other regions, such as Champagne, where “single plot Champagnes” are becoming increasingly popular among consumers.

Winemakers focus on minimal intervention to let the terroir speak through the wine. They believe in terroir-driven winemaking. Vinification techniques have evolved to adapt to the terroir, considering factors like tannin softness, maturity, acidity, and freshness.

It is also true for the aging techniques: The choice of aging method, whether stainless steel tanks for young, fruity wines or oak barrels for wines intended for aging, is vital in shaping the final product.

Navigating the Mystery of Burgundy Labels

Marie: “How does the AOC system help consumers identify wine quality, and is this system clearly reflected on the labels?”

Jean-Pierre: Understanding a Burgundy wine label can be challenging, as the information provided isn’t always straightforward. While the label will generally indicate “Burgundy,” it might not specify the grape variety, such as Pinot Noir or Chardonnay, which are the region’s staples. This expectation assumes that the buyer has a solid understanding of Burgundy’s wine industry and its labeling conventions. For Grand Cru wines, the label typically omits the village name, which can cause confusion, especially when a village’s name includes a renowned vineyard, like Gevrey-Chambertin. This might lead a buyer to mistakenly believe they are purchasing a Grand Cru wine when it is actually a village-level wine. Therefore, knowing the producer (the domain) is crucial, as it provides reassurance about the wine’s quality. Additionally, a deep understanding of terroir can significantly help consumers navigate these labels, as recognizing that a wine comes from a Grand Cru vineyard like Chambertin, for instance, signals its potential for greater complexity and aging potential.

The Soil’s Signature: Shaping Wine Style

Marie: “How can knowledge of terroirs help consumers choose a wine that suits their taste?”

Jean-Pierre: Knowing the terroir provides insight into the wine style and characteristics. For example, vineyards on clay soils produce powerful wines with rustic tannins in reds, while limestone soils yield wines with elegance, freshness, and minerality. Understanding the soil and subsoil allows consumers to predict the style of wine produced, making it easier to select a wine that aligns with their personal taste preferences.

Conclusion

Marie: “Thank you, Jean-Pierre, for this insightful discussion on Burgundy’s terroirs. It’s clear now that the AOC system is more than just a classification—it reflects Burgundy’s deep respect for the land. Understanding this connection between terroir and classification is key to appreciating the nuances of Burgundy wines. To conclude, could you name some of your favorite, most fascinating terroirs?”

Jean-Pierre: Identifying favorite terroirs is complex, but Pernand-Vergelesses “Sous Frétille,” facing the Corton hill and under the Frétille woods, stands out. Chevalier-Montrachet offers the aerial and mineral qualities characteristic of the Montrachet hill, and Musigny, Echezeaux, and the vineyards at the mouth of combes (valleys) also represent extraordinary terroirs.